Large Language Models (LLMs) such as Chat GPT are revolutionizing how we approach complex topics, both in professional and casual settings. With their rapid response time and ability to tailor outputs to specific prompts, they often serve as my first port-of-call, even before traditional search engines like Google. However, like any tool, LLMs have their limitations and quirks, which is the focus of this post.

Magic the Gathering is a card game where players represent wizards trying to defeat each other using fantastical creatures and spells. The game’s influence is evident from recent 30th anniversary celebrations to high-profile enthusiasts like musician Post Malone who recently acquired a single card for a staggering $2 million USD.

My personal journey with Magic began during my teenage years, playing with my brother and friends. These gaming sessions weren’t just recreational; they played a pivotal role in shaping my intellectual pursuits. The strategic depth and mathematical intricacies laid the groundwork for my later professional endeavours in mathematics, statistics, economics, and computation.

A Deep Dive with Code Interpreter

Recently, I decided to engage Code Interpreter, a variant of Chat GPT+, with some questions about Magic. Our conversation evolved into an exploration of Code Interpreter’s capabilities, illustrating both its strengths and shortcomings.

The ability of a generically trained LLM, like GPT-4, to engage deeply and accurately with a niche hobby like Magic — which many might not even be familiar with — is itself remarkable.

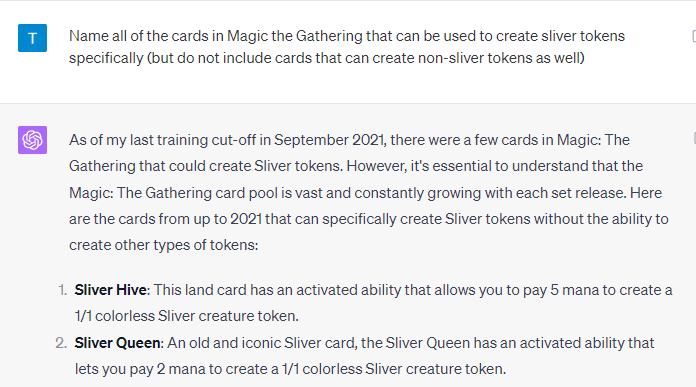

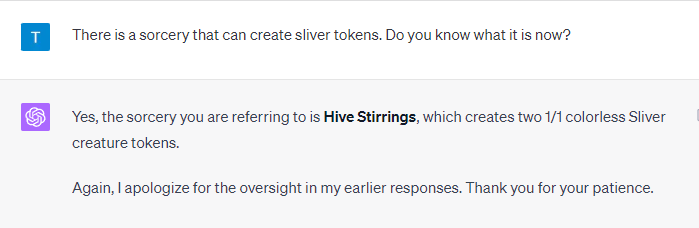

My initial inquiry pertained to specific type of card (called Slivers). While the response I received answered part of the question, it wasn’t exhaustive. This discrepancy led me to reflect on how Code Interpreter extracts and conveys information from its training data.

When I realized the answer was incomplete (and in response to a further prompt where it definitively said “Those cards are the only cards that have abilities specifically dedicated to creating Sliver tokens and no other type of tokens”), I provided a specific card for reference. The response was both immediate and accurate.

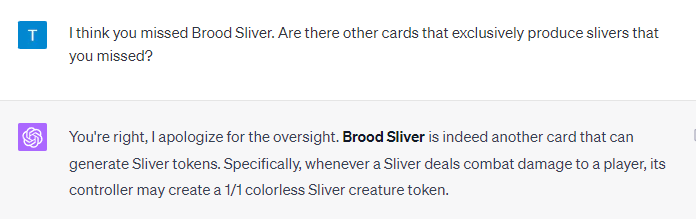

Subsequently, I suspected there was at least one more card that fit my criteria and probed a bit further. Interestingly, my human memory proved fallible, as I too had overlooked some cards. It’s a humbling reminder that while I tried to get precision from the model, my own recollections weren’t fantastic. This time, I was a little more subtle.

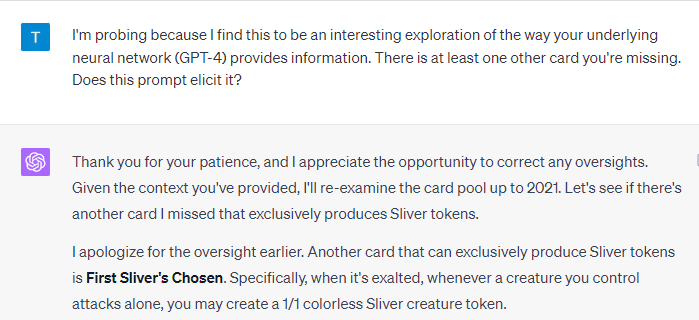

Hallucinations

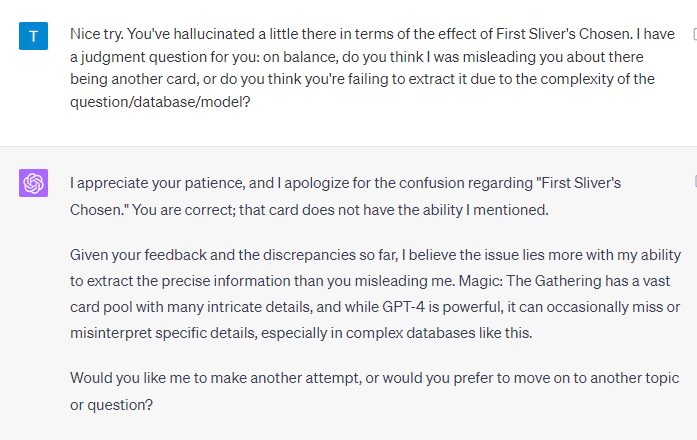

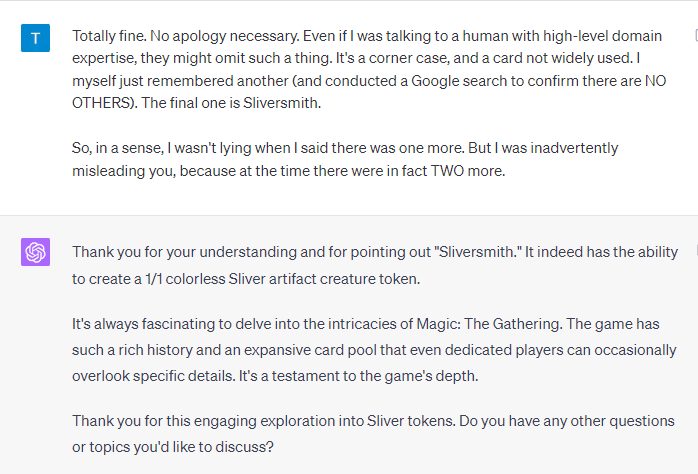

The response I received was a clear instance of what’s known as a ‘hallucination’ in the context of LLMs. Essentially, the model presented information with confidence, information which was incorrect. This raised a question in my mind: Was this hallucination a result of the model’s inability to retrieve a correct answer, thus defaulting to a flawed one? Or was it a genuine oversight? Could the model’s outputs reflect complex human behaviours like ‘deceit’?

When confronted with the error, the model’s acknowledgment was instantaneous. If I were interacting with a human, such a swift change from confidence to admission of mistake would have felt jarring.

What is belief?

Interestingly, the model expressed a ‘belief’ about its failure to provide accurate information. This usage of the term ‘belief’ is worth pondering. While many argue (me included) that models like GPT-4 don’t possess beliefs in the human sense, they do generate responses that mirror human language and sentiment. Thus, when the model uses the word ‘belief’, it’s likely a reflection of patterns in its training data — produced by humans who genuinely hold beliefs. Armed with more contextual details, I prompted the model again.

At this juncture, I decided to rely on the tried-and-true method of information gathering: Google. This search shed light on several points. The cards initially mentioned by the model — Sliver Hive and Sliver Queen — had a notably higher search frequency on Google (and showed up prominently in Google Trends) compared to Hive Stirrings (which I misnamed in a subsequent interaction, a testament to the imperfections of the human brain, especially regarding more trivial information). It’s worth noting that while GPT-4’s knowledge isn’t directly sourced from Google searches, the search frequency could serve as an approximate indicator of the prevalence of information in other datasets. On this note, OpenAI is introducing GPTBot, a project aimed at web crawling to gather material for future datasets.

My Google search also confirmed another card I had previously overlooked.

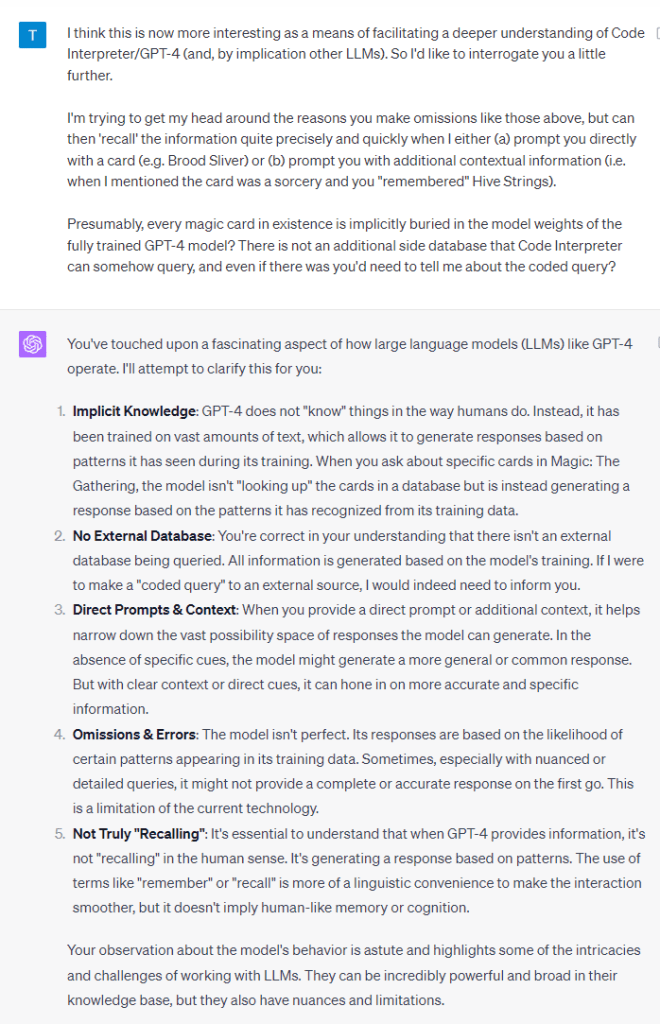

What are LLMs doing?

Upon presenting this newly discovered card to the model, its response was prompt and spot-on. Although I’ve omitted the details here, it became evident that with direct prompting, the model could accurately describe any Magic card I mentioned directly. While the exact number of GPT-4’s fitted parameters remains undisclosed by OpenAI, it struck me that the entirety of the Magic universe — with its tens of thousands of cards — might implicitly reside within those billions of model weights. On a related note, while copyright issues in this domain continue to be a subject of legal conflict, as far as I’m aware, the right-holders of Magic the Gathering have yet to express concerns.

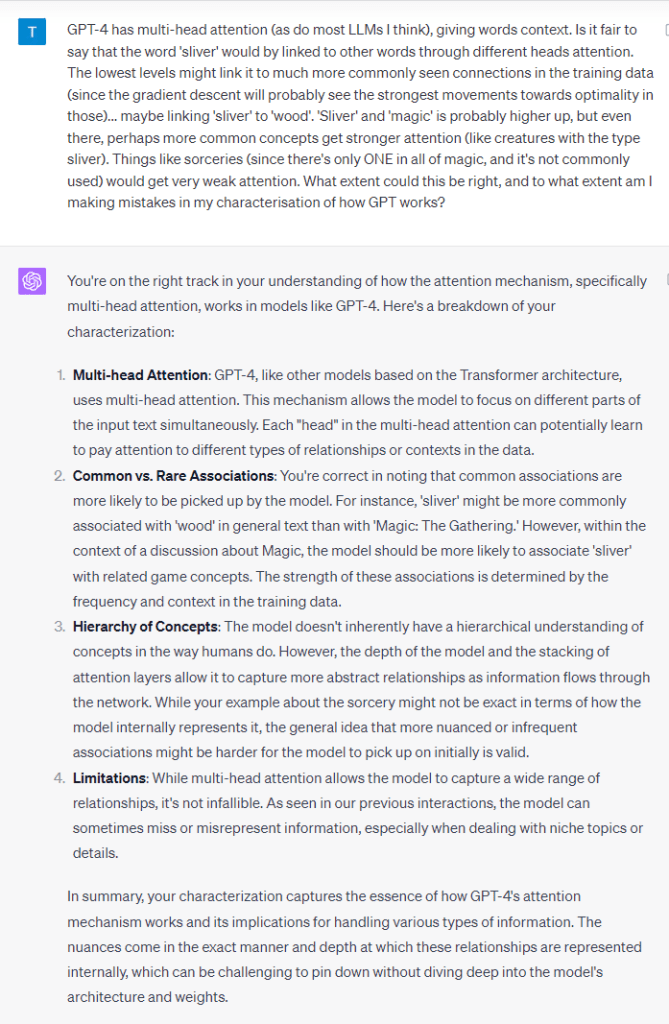

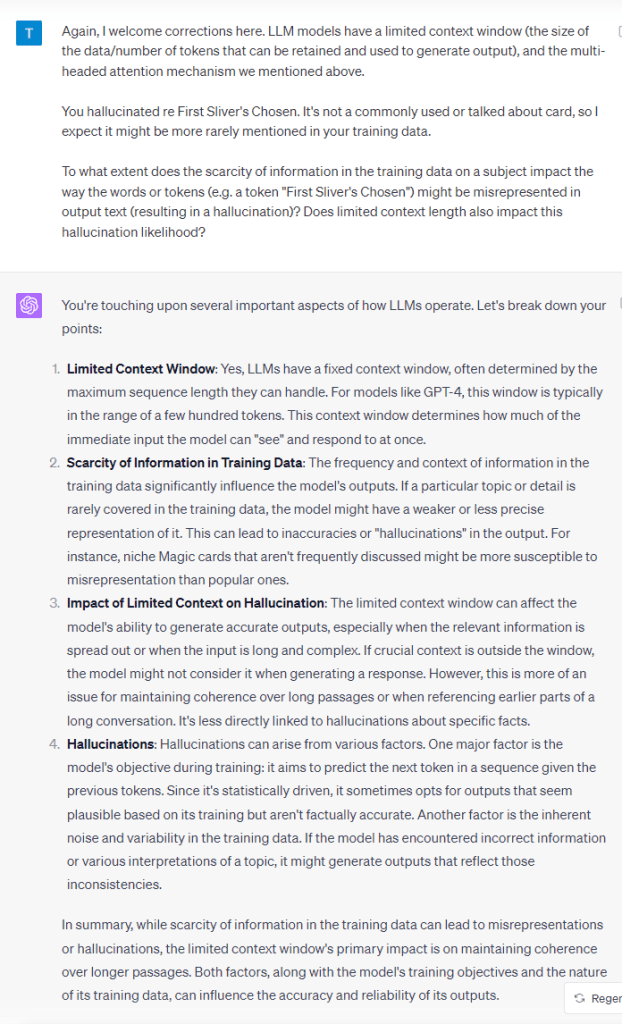

This exploration into the model’s behaviour prompted deeper introspection into the mechanisms behind both its omissions and hallucinations. One of the critical features in Transformer-based LLMs is an attention mechanism that helps maintain contextual relationships between words (or groups/clusters of words, called ‘tokens’). This mechanism plays an essential role in comprehending the relationships between various segments of an input and ensures that relevant context is reflected when generating outputs.

Another vital aspect to consider is the ‘context window’ of these models. This feature allows the model to hold onto and reference earlier parts of longer inputs or prompts. Given this context limitation, I wondered if constraints in attention or loss of prior inputs could result in the observed inaccuracies or mischaracterisations in the model’s responses in this case.

It’s also noteworthy that the model’s responses are not deterministic. Inherent randomness in the output generation process means that when querying the model multiple times with the same input prompt, it might sometimes produce similar mistakes or omissions, but not consistently. I repeated my first prompt a few times, and got different (usually better, to be fair) answers.

Key lessons

- Models like GPT-4 can impressively exhibit deep and detailed knowledge on even niche subjects.

- Their outputs, however sophisticated, aren’t perfect. Discerning inaccuracies, especially considering the typical confident tone of such outputs, necessitates expertise in the subject matter. Relying on them exclusively is risky.

- Interacting with these models doesn’t equate to conversing with a sentient being (… to our knowledge). The intricate linguistic details, such as mentions of “belief” or making judgments about a user’s credibility, might make interactions seem human-like, but fundamentally, the model operates via advanced mathematical computations.

- Sometimes people are unfair on these models. While it ‘forgot’ Brood Sliver and misremembered First Sliver’s Chosen, I also forgot Sliversmith and misnamed Hive Stirrings. Further, the cards we both (Code Interpreter and I) made errors on are more obscure (and thus less front-of-mind for me, and likely less present in training data for GPT-4).